The seemingly improbable but not impossible task I've taken upon myself is explaining it in the simplest terms possible to laymen such as the very important group known as Philosophers, whose contributions are badly needed in the world today ... provided it's the proper form of Philosophy known as Aristotelian Logic.

|

| Captain America, Jack Sparrow, and the Norse god Thor all made appearances during the advertising spots at last night's Super Bowl |

And OK, that's that. The Super Bowl is sort of annoying because the commercials are often better than the game, so much so that one finds it hard to take a break! Super Sunday is well noted at least here in the States as Madison Avenue's "coming out party," meaning the long versions of often comical television ads that will be shortened in the weeks and months to come such that you have to watch and can't miss a minute.

"Advertising", that is to say self-promotion by various Academics at the cutting edge of Mathematical Physics is annoying, on-going, and human nature, so we'll never be rid of it alas. Alas, so don't worry about things you cannot change, as the Serenity Prayer advises, so we won't.

On the upbeat side, there are certain maths that cannot be debated since they have been experimentally verified, so let's begin:

Wikipedia, as usual, has a technically correct although aggravating in its usual (in mathematics) boring "watching paint dry" description of U(1), also known as the Circle Group, which describes Electromagnetism and Quantum Electrodynamics (QED Theory).

It all begins with the Math so let's get started.

(Note: I will begin this morning with the cut'n'paste job of Circle Group from Wiki, but will add much more to this post and would do so now except I have many chores to do during this working day so we'll see you again tonight or tomorrow morning.)

The electric field vectors of a traveling circularly polarized electromagnetic wave.

CIRCLE GROUP

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from U(1))

For the jazz group, see Circle (jazz band).

| Lie groups | |||||||

| |||||||

The circle group plays a central role in Pontryagin duality, and in the theory of Lie groups.

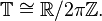

The notation T for the circle group stems from the fact that Tn (the direct product of T with itself n times) is geometrically an n-torus. The circle group is then a 1-torus.

Contents |

Elementary introduction

One way to think about the circle group is that it describes how to add angles, where only angles between 0° and 360° are permitted. For example, the diagram illustrates how to add 150° to 270°. The answer should be 150° + 270° = 420°, but when thinking in terms of the circle group, we need to "forget" the fact that we have wrapped once around the circle. Therefore we adjust our answer by 360° which gives 420° − 360° = 60°.Another description is in terms of ordinary addition, where only numbers between 0 and 1 are allowed (with 1 corresponding to a full rotation). To achieve this, we might need to throw away digits occurring before the decimal point. For example, when we work out 0.784 + 0.925 + 0.446, the answer should be 2.155, but we throw away the leading 2, so the answer (in the circle group) is just 0.155.

Topological and analytic structure

The circle group is more than just an abstract algebraic group. It has a natural topology when regarded as a subspace of the complex plane. Since multiplication and inversion are continuous functions on C×, the circle group has the structure of a topological group. Moreover, since the unit circle is a closed subset of the complex plane, the circle group is a closed subgroup of C× (itself regarded as a topological group).One can say even more. The circle is a 1-dimensional real manifold and multiplication and inversion are real-analytic maps on the circle. This gives the circle group the structure of a one-parameter group, an instance of a Lie group. In fact, up to isomorphism, it is the unique 1-dimensional compact, connected Lie group. Moreover, every n-dimensional compact, connected, abelian Lie group is isomorphic to Tn.

Isomorphisms

The circle group shows up in a variety of forms in mathematics. We list some of the more common forms here. Specifically, we show thatThe set of all 1×1 unitary matrices clearly coincides with the circle group; the unitary condition is equivalent to the condition that its element have absolute value 1. Therefore, the circle group is canonically isomorphic to U(1), the first unitary group.

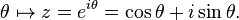

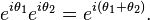

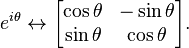

The exponential function gives rise to a group homomorphism exp : R → T from the additive real numbers R to the circle group T via the map

If complex numbers are realized as 2×2 real matrices (see complex number), the unit complex numbers correspond to 2×2 orthogonal matrices with unit determinant. Specifically, we have

Properties

Any compact Lie group G of dimension > 0 has a subgroup isomorphic to the circle group. That means that, thinking in terms of symmetry, a compact symmetry group acting continuously can be expected to have one-parameter circle subgroups acting; the consequences in physical systems are seen for example at rotational invariance, and spontaneous symmetry breaking.The circle group has many subgroups, but its only proper closed subgroups consist of roots of unity: For each integer n > 0, the nth roots of unity form a cyclic group of order n, which is unique up to isomorphism.

Representations

The representations of the circle group are easy to describe. It follows from Schur's lemma that the irreducible complex representations of an abelian group are all 1-dimensional. Since the circle group is compact, any representation ρ : T → GL(1, C) ≅ C×, must take values in U(1)≅ T. Therefore, the irreducible representations of the circle group are just the homomorphisms from the circle group to itself. Every such homomorphism is of the formGroup structure

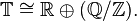

In this section we will forget about the topological structure of the circle group and look only at its structure as an abstract group.The circle group T is a divisible group. Its torsion subgroup is given by the set of all nth roots of unity for all n, and is isomorphic to Q/Z. The structure theorem for divisible groups tells us that T is isomorphic to the direct sum of Q/Z with a number of copies of Q. The number of copies of Q must be c (the cardinality of the continuum) in order for the cardinality of the direct sum to be correct. But the direct sum of c copies of Q is isomorphic to R, as R is a vector space of dimension c over Q. Thus

See also

- Rotation number

- Torus

- One-parameter subgroup

- Unitary group

- Orthogonal group

- Group of rational points on the unit circle

References

- Hua Luogeng (1981) Starting with the unit circle Springer Verlag.

1 comment:

Thanks for this. I really like what you've posted here and wish you the best of luck with this blog and thanks for sharing. Sites like backpage

Post a Comment